Giant Backlog of Photos I: Mongolia

Note from 2017: Frustration with Blogger caused me to flee to Google Photos’ superior photo-displaying capabilities. Migrating to Jekyll has allowed me to bring the photos back here to the blog. Which is just as well, since the Google link died.

Since nobody seemed to have an opinion strong enough to mention, I’m going to go about putting up the photos from my travels in whatever way I see fit. I’ve already written about all these trips, but some of the photos require a bit more explanation than you can get from what I wrote. So I’ll write new explanations for the ones that need it, and I’ll copy-paste bits of the old blogs where I can, so I don’t have to write stuff all over again.

Our first stop (if you’ll look out the left-hand windows, keeping your arms and legs inside the vehicle) is Mongolia. I’m going to do this a bit differently than I have—I’m linking you to an album I made, so you can see all the pictures at large size with the captions right there. [Link no longer goes to an album on a different page, but just to lower down on this page… but you can still see the pictures large with captions, just click on the first one and a gallery will pop up.] Anything in quotes is from the post The Steppe and the Desert, unless it says it’s from my journal, in which case it’s from my journal, and it’s brand new to you. Anything not in quotes is stuff I just wrote. You’ll have to forgive the crud on my camera lens. These photos aren’t going to win awards—this is why I had a new camera on my Christmas list that year. Anyhow, enjoy! I’ll be back with more photos when I get around to it.

The Photos

Arriving to Ulaanbaatar. “… I got myself a taxi to town. The taxi driver kind of ripped me off, I think, but it was okay, because on the way he handed me a little 50mL bottle of something called arkhi, which turned out to be a lot like whisky, and pretty enjoyable; I was encouraged to take a swig in the car. We passed lots of billboards for mining equipment and investment in mining.”

“I stepped inside the State Department Store to look around. I only looked at the first floor, but it’s a weird place. It’s like a mall, except all shuffled together. You enter through what looks like a JCPenney, but then if you keep going straight there’s a little stairway and a swinging gate and you’re in a grocery store section. Next to the grocery store, just through a doorway, is something that seems like the kitchenware section of Walmart.”

This is the building where, I believe, the entire government is located. Front and center is a statue of who else but Genghis Khan, far and away the country’s most beloved historical figure. Everything is named after him, including not one but two brands of vodka.

From in front of the Khan, you can see downtown Ulaanbaatar. The equestrian statue is of Sukhbaatar (literally, “Ax Hero”), a much more minor historical figure who seems to get recognition largely because Mongolia doesn’t want to give the impression that its only personage of note died in the 1200s. The big blue building is the Blue Sky hotel, shaped like a huge fin, but you can’t tell from this angle.

The rest of the city isn’t so glamorous. It’s the sort of place that Batman outsources his legal work to.

It’s also the sort of place where you can get your hair and beauty expertly destroyed.

One other thing Ulaanbaatar has is a place called Gandang Monastery. Mongolia is pretty tolerant of religious diversity, but Buddhism might be the most important one, and in fact Kublai Khan (Genghis’s son) had a hand in establishing the position of the Dalai Lama.

They’re building a giant Buddha statue. This is how far they’ve gotten.

From behind the feet you can see the vicinity.

These are mantra wheels. As you walk past them, you turn them with your hands and thereby “say” Buddhist mantras. The symbols are characters from an alphabet created by a Mongolian monk named Zanabazar to write Mongolian.

For all the glamor of Gandang Monastery, though, go off a hundred yards or so to the side and you’re out in the slums.

Mongolian slums look different from most: a patchwork of high-fenced enclosures, each usually with a ger (yurt) inside, although here they seem to be houses.

“The Selbe Gol is a small river, more of a creek really, but with a floodplain much bigger than a creek’s. It heads north out of town, so I did too. I had to cross town to get to it, going through the fancy-suited business district on the way; when I found it, I had reached a poor district. Everything was run-down buildings and signs for auto repair and convenience stores. And gers here and there. … Along this street things continued about the same for a long time, though the gers became steadily more plentiful, until they were finally almost the only thing along the road, all behind fences with geometric knot designs on the gates. … I took a side street that went through the gers and ended up there in the floodplain. [Journal.]”

“[After a while] there were a lot more people out and about. I eventually stopped at a truck marked 생생한우 [fresh beef], and explained the meaning of that (by mooing) to the five people sitting in its shade. I sat down and we got to talking a whole bunch. They poured me vodka. Mainly I talked with a guy named Dashka; also a Dabkharaya and a Naagii. They thought it was swell that I was American, and gave me cream horns from their bakery. And we got to know each other a bit. It was pretty darn cool. [Journal.]”

Not all the gates had geometrical knots. This bear is from a Soviet children’s cartoon.

After a few days burnt in Ulaanbaatar, I finally got on board with a tour that left the city. “Our driver wound us expertly through Ulaanbaatar traffic and out to a road overlooking the brown bubble of smog that encloses the city.” [Journal.]

“There are a few things that make the steppe the steppe. The first one, and the most salient one, is its infinitude. … Once you get outside the city, and you can no longer see the disgusting brown haze that completely envelops it, you can stand anywhere, turn 360 degrees, and see nothing but horizon. There are no trees, no bushes taller than your knee, in many places no hills or deviations from complete flatness, and quite often no buildings.”

A Mongolian-style cairn, called an “ovoo”, with scraps of blue fabric left by passing travelers.

“Another thing you don’t know about beforehand is the strange distortion of time that happens there. Boogii told us that in the city, and in other countries, there are twenty-four hours, but in the Mongolian countryside, there are two: morning, and afternoon. Night doesn’t count as a third hour, because everyone’s asleep. When you do run into people out there, they are supremely unhurried people. Nomadic Mongolians must have more free time than practically anyone else on the planet. What is there to do? Have a bit of breakfast. Get on your horse and herd some animals around, if they need herding. Make some lunch. Sit around and talk. Watch the clouds, because you probably don’t have a TV, or even electricity. Make some dinner. As a consequence, the pace of our trip was something that took some getting used to. Our first lunch was at a square building, near a few gers but otherwise completely alone in an expanse of nowhere, and we were a bit surprised to find out that it would take an hour for the food to be ready. That turned out to be one of our quicker meals, actually. I think it might have been a bit ahead of schedule. Most of the meals took more like an hour and a half. We got used to this.”

“We stopped at a congregation of monoliths with ovoos scattered all around, and took pictures, as tourists do.” (Journal.)

We stayed most nights in tourist ger camps. It’s the same concept as a hotel but instead of a room connected to others by a hallway, you get a bed in a ger shared with however many other guests fit in it.

Mongolian doors are about four feet high to keep warm air in, and almost always beautifully decorated.

Then back to the vastness of the steppe.

“Towns here aren’t how you’d think of a town. They’re a few buildings that all seem to be food stores, and one pharmacy and a few unidentifiable ones, maybe with satellites and towers outside. The people live in a few gers scattered around the perimeter.” (Journal.)

And there’s not much separating them from the expanses that surround them.

A highlight of this town was that I got to see a ger being put up.

“There are other things you wouldn’t even have guessed at. One is the smell. The first time the van stopped, I stepped out into a stiff wind and took a deep breath, and there was an unmistakable scent to it, surprisingly definite, not like a vague, shifting collection of faint smells, more like something you’d drink as an herbal tea. Eventually, I found the plant responsible. It has lacy triangle-inspired leaves and hard stalks that sprout out yellow ball-shaped flowers. I asked Boogii what it was called, and he thought for a moment and told me: агь (pronounced ‘aig’). This turns out to be wormwood, the same stuff they use to make absinthe. It’s hard to describe a smell, but maybe you could say it’s somewhere between chamomile and cilantro. Every time I was outside, it was there to greet me. It was interesting to realize that the steppe must have smelled like this for millions of years. An eternal smell.”

Watering trough.

Herding goats by motorcycle.

“The Flaming Cliffs appeared around 11:30. I didn’t know what to expect—come to that, almost everything we’re doing is going to be a surprise for me—but they were pretty good. It was odd that they were out there in the middle of a broad flat void. Something, or someone, said this was where they found the first dinosaur fossils in the country, and I could see why it would be easy to find them: the cliffs were made completely of crumbly dirt, and any fossils would stick right out. But the crumbliness of the dirt made the cliffs seem less eternal than cliffs usually do, more impermanent.” (Journal.)

I don’t remember what dinosaur this was; possibly a velociraptor.

Arriving at Yolyn Am (Vulture Valley), we got into a traffic jam.

“When we got there, it had started to rain. But we put on raincoats (Kyle took an umbrella) and got walking. None of us knew anything about it beforehand except that it’s supposed to be really scenic.” (Journal.)

“It turned out to be an incredible valley. Black rocky cliffs completely surrounding us, rugged and nearly vertical and tremendous. And where we were walking: a grassy path with a peaceful stream running through it. Everyone loved it.” (Journal.)

I, for one, felt like a member of the Fellowship of the Ring.

In these cliffs lives the pika, cousin of the rabbit. They shout in a shrill voice when they run off.

After a night in some very poorly heated cabins, we left the valley and its clouds behind.

About 2:00 on day four we arrived at our place for the night, a collection of gers, and I finally thought to take the picture of the inside of one. This is a tourist ger, as you can tell by the lack of any home furnishings besides beds and a table and stool.

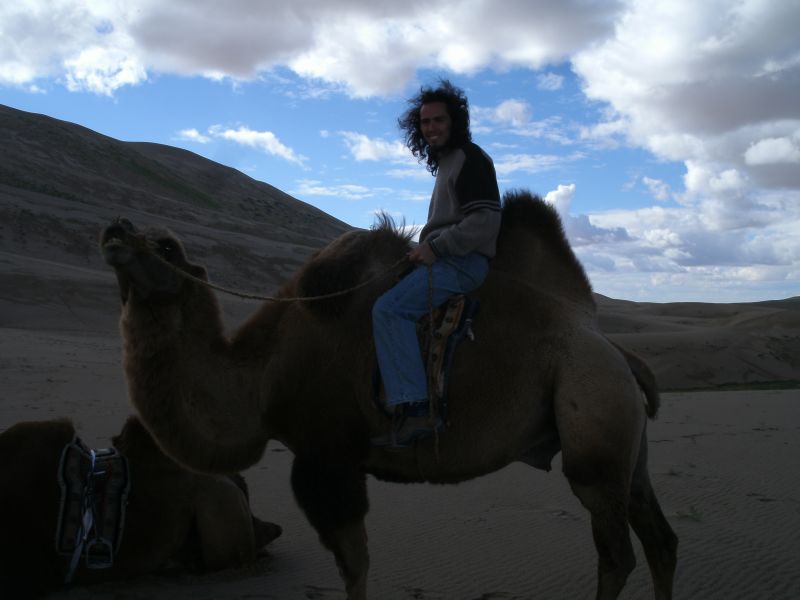

“These gers were sitting at the bottom of a big dune, not right up next to it, but about a camel ride’s distance away. And coincidentally, there were also a bunch of camels there. This was our agenda for the afternoon.

[We] each picked out a camel from a group that a hardy old lady led over to us. The camels all dutifully sat down and let us get on, and the man of the ger, Nyamka, chained them all together using camel-hair ropes fastened to homemade wooden bits pierced through their noses.”

This is actually Nyamka’s hardy old mother and his wife, I believe.

Kyle, John, and Crystal, pleased to be on camelback.

The winds on the dune whipped the grasses around and made them sweep a radius clean around them.

Now you know what I look like on top of a camel.

“Nyamka dropped us off at the very foot of the dune [and took the camels back]. It was cold: we were in the shade, and nighttime was coming on, and it’s getting to be fall in Mongolia, land of some of the harshest winters around. (Ulaanbaatar is the coldest capital city in the world.)

But here we were at this sand dune, and what else was there to do but climb up it? Everyone gave it a go. The dune was way taller than it looked. Not only the steppe magnifies distance—the dunes do too. And also, sand isn’t good for climbing. It causes you to slip backward half a step for each step you take. We all took several breaks for catching our breath and swearing vividly. Crystal and John turned back partway up, figuring they’d gotten the idea. That left me, Kyle, Jenna, and Rüdiger to claim the top.”

“So we powered on, and claim it we did.” When we got to the top we could see for even farther than usual, including this storm coming in to our camp from behind us.

“The wind was beyond anything I think I’ve known before. Maybe it wasn’t actually the fastest I’ve felt, but what it was was full of sand. All of it blowing in hard swirls and eddies that all seemed to direct themselves right into my face. I squinted out at the other side: dunes, dunes, dunes, all of them smaller than the one I was on, but stretching out, as so many things do in this country, to the edge of vision. Kyle and Rüdiger showed up and looked out, and so did Jenna, but none of us said much because sand would have gotten in our mouths. Then we universally agreed that it was time to climb down.”

“Jenna and Rüdiger took the safe way, switchbacking down the way we’d come up, approximately. Kyle and I went directly for the steepest section, pitched at some absurd angle like sixty degrees. At this angle, every step was as good as three or four, or maybe ten. There was the initial step, and then there was the sand giving way for several feet underneath that step, until I had dug in deep enough to stop. Apparently, when people dream of flying they dream it in several different ways; John and Jenna and I found this out one night while we were talking. John has certain places in the world where he can fly, and Jenna can fly by jumping off of high places. But when I fly, it’s by running faster and faster until I take off. Each pace gets longer and longer until I’m in the air for several seconds at a time, dozens of feet per stride, and finally I realize I don’t need to touch the ground after all. Running down the sand dune was the only time I’ve felt like that was happening in real life.”

“Once I woke up by hitting the bottom of the dune and walking back to camp thoroughly exhausted, I found there was yet more in store for us tonight. For one thing, tonight, Nyamka would be branding a few of this year’s foals that he hadn’t branded yet. He did this before dinnertime and we all came out to watch. All the foals were tied up to a rope strung between two short logs hammered into the ground; so were their mothers, I think. He picked out the smallest foal first, and Boogii came over to help him. Nyamka grabbed the foal by its neck and wrestled it for a while, then got the right grip on it—right hand around its neck, left hand grabbing onto some skin on its belly—and then he lifted the whole foal off the ground, turned it over in mid-air, and landed it in a lying-down position on the ground.

Now he kept a leg on it so it couldn’t get up, and he and Boogii tied its strong, flailing legs all together with a piece of rope, hobbling it. What an utter mass of muscle Nyamka was. And he was middle-aged. With that foal stabilized, he picked out a bigger one and wrestled it down the same way. Meanwhile, the hardy old lady from before had been heating the brand in a pile of dried horse dung, and by now it was good and hot. Nyamka got a mouthful of water from a dirty bucket and took the brand over to the first foal. Carefully, he chose a spot and pressed the brand deliberately against the foal’s skin for several seconds, then took it off and spat the cold water all over the burn. The foal hardly even flinched. I was amazed. He branded the second foal, then untied them both, and neither one went on a kicking rampage. They were calm, almost, no different except that they were sporting a new design on their flanks.”

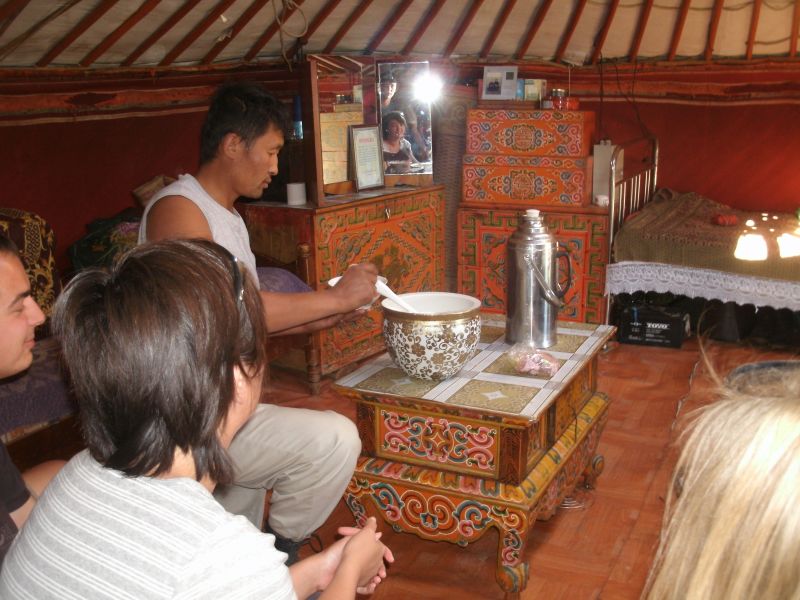

“He branded one more the same way, and then it was time to make dinner. The first step to that was to kill the goat. I didn’t realize a goat was being killed until some of the others came in and told me Nyamka had just killed it, but I came right away outside and saw John helping Nyamka carry it over to his ger. John and I both helped him cut it up. John stabilized it for a little while at the beginning while Nyamka cut its skin away, but I spent a bit longer, holding onto its front legs while he cut it open and pulled out each of its organs. The stomach was enormous, probably accounted for half the volume of its innards. Maybe that’s to do with how it’s a grass-eater.” [Cont’d next photo…]

[…Cont’d] “The cavity started filling with blood, which he scooped up with a bowl and emptied into a bigger bowl in order to make blood sausages later. After he got each piece of meat off, he laid it on top of his ger. He was highly efficient. While he was cutting it apart, I thought I could feel its nerves still humming under my fingers. It was weird, unforgettable.

Nyamka kept most of the meat, since a whole goat is a bit much for all of us for one night. But we did have some of its ribs in our soup that night. It was pretty much the shortest supply chain that any food I’ve eaten has ever had. I went to bed feeling highly satisfied with the day.” (Journal.)

One of the gers at Nyamka’s camp. This is the thoroughly modern nomad’s standard setup.

One day we passed a school. The kids were out on the basketball court playing a game whose rules I couldn’t fathom.

One of many ruined monasteries dotted around the countryside. When the Soviets took over Mongolia, they took it upon themselves to get rid of any traces of Buddhism. That didn’t work entirely, but a lot of once thriving monasteries are now dead, so they certainly had an effect.

“We headed off toward Orkhon Waterfall on the typical dirt tracks. Shortly after we got going, Boogii asked if we wanted to try airag (fermented mare’s milk). Sure, we said, so he pulled off at a ger of some people he didn’t know. But he knew they’d have airag because of all the horses they had.” (Journal.) They also had these tiny baby yaks. Isn’t this about the most adorable ungulate you’ve ever seen?

“An old lady welcomed us inside with typical Mongolian hospitality and sure enough there was a pot of cold airag for us. Boogii took a big bowl first, and then we all split a little bowl among us. Crystal tasted it first and said it tasted like permanent marker. When it got around to me, I had to agree. This is one part of Mongolian culture I won’t be adopting. But John had a whole bowl. As he was finishing, Boogii explained that on the first time you should only take a sip, or you’ll get the shits, or at least that was his personal experience.” (Journal.)

“Out front, the old lady was drying some sour cheese on her roof, and we tried that.” (Journal.) This visit was followed by Crystal’s disastrous allergic reaction to the airag, which doesn’t really have a place in these captions, so you should go read it at the original post if you want to.

Orkhon Waterfall, which we did eventually reach.

Audrey insisted that we go visit Tövkhön Khiid, another once-ruined monastery, now restored. “Boogii drove us to the top of the mountain [that it’s situated on]. Now, this is not a normal thing to do. The trail to the top was not a car trail. It was barely even a four-wheeler trail. It went through a forest, and trees were always getting in the way of the van. The trail surface was more rutted and pitted than any other surface we’ve driven on so far. Every few minutes, we hit an obstacle that looked absolutely impossible—a mud pit, a hairpin turn. But Boogii was a champion and drove it all anyhow. Even though we weren’t really enjoying getting bumped to pieces in the back. It was absurd. But we got to the temple, anyhow.” (Journal.)

The inner gate.

“It was surrounded by blue prayer flags, and built into rock all the way up to the very peak. At the bottom of the rocks making up the peak, there were a few brightly-colored temples. One of them had a monk inside who told me a little bit about the various artifacts inside, though he basically knew not a word of English—and I’m not even sure if he knew Mongolian; he may have been Tibetan. Above the temple, accessible by scaling up a rock wall, were the caves and the ovoo” (Journal), which is what this picture shows. “Women weren’t allowed to the ovoo on the very top. Shame—there was a terrific view, and it was a big, neat ovoo. I took some pictures for Audrey.” (Journal.)

On to Kharkhorum, the walled city that was the capital of the ancient Mongol Empire.

This is the Mongol Empire at its peak, with present-day Mongolia in blue.

Temples in Kharkhorum.

A man prostrates himself before the memory of the grandeur of the Khan’s great city.

An ancient turtle keeps guard.

Audrey strikes up a conversation with some young monks-in-training.

At our ger camp next to Kharkhorum we watched a man play traditional Mongolian instruments like this horsehead fiddle (look at the headstock) and do throat singing.

“Today’s destination turned out to be Khustai National Park, the place where the takhi, the wild horses, live. I wasn’t particularly interested in seeing wild horses, but once we got there, I got a bit excited, though gradually. We all watched an informational film first; it looked it was made by a community college filmography student, but it had good pictures of all the wildlife the park has. After it finished, we gained a guide—a college girl—and drove off into the park.

Our guide turned out to be a bit useless. She pointed to some marmots, but then she was silent a long time. but then she did notice some horses. There they were, up on top of a hill, one of the many hills we were driving among. [Cont’d next photo…]”

“[…Cont’d] We got out and walked toward them, but stopped at the regulated 300-meter distance from them. they were just resting there, peacefully. The ancestors of the modern horse—only a few hundred of them left in the world. ¶ A little farther along, we saw a much more impressive sight. There was a herd of ten or so, and two of them were fighting. Like, seriously going at it, chasing each other up and down the hill at a gallop, kicking to injure. Aside from seeing a wolf catch a takhi, it was about the most exciting thing I could’ve hoped to see today. I was pretty impressed.” (Journal.)

A deerstone, erected and painted a thousand years ago or more with a design that no anthropologists have been able to unambiguously explain. The general sense is that it’s probably a spiritual design to do with the hunt. It shows a deer, though it’s hard to tell without actually getting on your knees next to the stone.

And then we came back to the city, the whole happy group: John, Crystal, Audrey, Boogii, Kyle, me, Jenna, and Rüdiger.

After the tour, I took my own self-guided trip. I got a bus to a town a little ways away from Ulaanbaatar called Zuun Mod (Hundred Trees) and just started walking.

Another ruined monastery, called Manzushir. This one never had a chance, being so close to the capital. I believe this was also designated the first national park in Mongolia.

After poking around Manzushir a little, I walked off into the countryside, just waiting until I saw a ger. “I walked over a hall and sure enough there was someone on horseback herding goats and sheep. I walked down and found the woman of the house with her feet on the ground while her husband herded on horse. It was awkward being unable to communicate, but eventually we managed to understand that I’d like to have a meal and sleep on their land, per the Mongolian rule of hospitality. It really is true—they open their homes to everyone.

I sat in their larger ger, up on the hillside, while she gave me food (meat and ‘salat’, a vegetable mixture) and we tried to communicate. I gave her a flashlight for the food she was going to cook, which was khorkhog, though it turned out to be more like tsuivan. [Cont’d next photo…]”

“[…Cont’d from last photo] By the time she finished, her husband was back, so we all ate together while quietly watching a TV show called ‘Funny Music’ where contestants memorize a song and then try to sing along, but if they forget, they get aluminum pans dropped on their heads. … To get to the lower ger where I’d be sleeping, I did something brand new: I herded goats and sheep. It turns out to be really easy. You just walk behind them and make noise, and they walk ahead. Still, I felt really accomplished. With them pent, she went on to milk their two cows. She gave each cow’s calf a little time on the udder first, then tied the calf away and milked into a bucket. Don’t know what she did with the milk. ¶ Around 8:00, when it got dark, it was about time to think of heading to bed. They lit a fire in the stove in the little ger, and we communicated a little. I showed them pictures, and took a picture of all of us.” (Journal.)

The next day, I wandered the hills, finding this giant bug and accidentally taking a long loop that brought me back to that couple’s ger. “I crested a hill and met an old lady who was herding goats. I offered to help her and she said sure, so I herded them with her down halfway toward her ger at the bottom of the hill. Then she said that was good, and invited me inside for some milk tea. Her ger had a lot of horses, a few dogs (one very dedicated, and leery of me), and a young woman with ridiculously red cheeks and a big smile. The inside was alive with flies, all wanting the dairy being made in there. The woman gave me not just milk tea but also something that turned out to be extremely hard but also very tasty dried cheese, and also some yogurt that was fresh from today. I got the first bit, except for a spoonful of starter that the lady put in a bag by the door. It was really good. [Cont’d photo after next…]”

[While wandering the hills, I found this impression of a ger from a previous year.]

“[…Cont’d] I thanked them and wandered off up a hill. This brought me into an expansive, long valley with something resembling agricurture, but also a few gers. I walked down to the other end of it, I was pretty sure, but I still had time, so I crossed into other valleys by clmbing hills. It seemed like I never hit the same valley twice. In one of them, I found a mine, completely by surprise. I walked a very long time and got very tired. Eventually I found a promising ger. I was hesitant at first because there were cars—maybe they’d be modern types who’d insist on cash, which I didn’t have?—but I stopped in and got a cordial welcome by a guy named Myagmarjav. [Cont’d next photo…]”

“[…Cont’d] He and his wife, Purevsuren, live there with his parents, Sanduijav and Khandsuren. Sanduijav was almost completely bedridden. But he could still talk a mile a minute and frequently did. It wasn’t as awkward for me at Myagmarjav’s because when I wasn’t talking they all had each other to talk to, plus visitors now and then. They gave me lots of milk tea and some buuz (dumplings) and bread from earlier. It wasn’t a hot meal, I guess, but it was still great, enhanced by the hospitality. I answered questions about me and my trip and just sat and watched and listened awhile. [Cont’d next photo…]”

“[…Cont’d] After dinner Myagmarjav, Khandsuren, and some other guy milked all the cows, at least seven of them I think. They lent me a deel (coat) so I could watch without freezing. After they eventually finished, they brought all the milk in and boiled it. Around then it got to be time for bed. Myagmarjav and Purevsuren gave me their own bed and slept on the floor. Now that’s hospitality. Everyone chatted awhile, especially Sanduijav, and eventually we fell asleep. [Cont’d next photo…]”

“[…Cont’d] This morning started around 6:00, but Myagmarjav told me, ‘Unt! Unt!’ (‘Sleep! Sleep!’) while he was getting the fire ready. I did get up a little later, of course, and had milk tea and bread with fresh butter skimmed from the top of a bowl of milk they had off to the side. Awesome. Everyone chatted, including two other guys named Myanginbayar and Ganbaatar [in the photo] who showed up. I packed up and was about to leave, but they all told me to stay for ‘khool’, a meal. So I had pasta and beef, plus more bread and butter. All good. I gave them a pocket knife and finally set off toward Zuun Mod.” (Journal.)

And then I rode back to Ulaanbaatar and soon I got on the train for Russia. But that’s next update.

File under: photos, Year of Adventure · Places: Mongolia

Note: comments are temporarily disabled because Google’s spam-blocking software cannot withstand spammers’ resolve.

4 Comments

Anonymous

HistoryThe Mongolian pictures were superb. Exactly what I wanted to see. Beautiful landscapes. G.Pa.

Anonymous

HistoryExcellent!

Dave

Anonymous

HistoryWow, amazing. -Mom

Anonymous

HistoryWow! It is so much better when you have pictures to go with the journal. I'm so happy you have all that, and I'm looking forward to the next bunch. Amazing stuff. Grandma