Changing My Blog to Jekyll: Why I Did It

or, Getting Right with Technology.

(For those who don't code.)

This is the first of two posts about redoing my blog, although the other one will be aimed at a different audience, mostly consisting of programmers trying to do the same thing I did.

I’m aware that I promised to write about sugarbush. My time there turned out not to be a solid week but several discontinuous days, and I haven’t yet spent all the time I’m planning to spend there. I’ll write when I have, but meanwhile I’ve been wanting to write this.

I’m going to take on a bit of a challenge: I’m going to try to make some very nerdy programming stuff interesting to regular people, people who have no interest in code other than that it should work—even people who fear code and want nothing to do with it. I’m going to try to explain why I spent what probably totaled up to at least a full work week, and maybe two, reprogramming this blog from the ground up. Bear with me; I really am going to attempt to put in some ideas that you have a chance of caring about.

You may know that I’m planning to move off the grid soon. Misty and I have had this plan for years, but only recently has the realization gradually snuck up on me that this is a very big change in my life. Over the last couple months I’ve been working on moving mentally, so that when I move physically I won’t leave myself behind. Strangely enough, spending several dozen hours elbow-deep in code has been a part of that process. Let me explain.

The more you learn about computer programs, the more you should distrust them. And in my job as a code monkey, I’ve spent the better part of the last three years learning a lot about computer programs (often things that I had no job-related reason to learn about, just because they seemed interesting). If you use computer programs like most people do, and have no particular curiosity about what’s going on behind the scenes, our society’s collective technosystem probably looks fairly stable to you. Beyond the occasional crash, most programs you use do what they’re told, and they do it consistently, and the little colored icon squares you use to get to them show up reasonably close to on time when you wake up your phone or your computer.

Just getting to that point was hard won. It’s true, computers do work pretty well for the things

that a lot of people really want to do: edit documents, get directions, read email, watch porn

videos. But consider what it took to achieve that: millions of man-hours; the creation of an entire

new industrial sector; concomitant factories in poor areas of distant countries; a purgatory period

of many years in which computers existed but were useless for everyday purposes to all but the most

advanced of nerds; and a drastic shift in the balance of global industrial systems. But hey, now you

don’t have to do long division anymore.

(And even with these common things you can see problems creeping in from the edges. Microsoft Word encountered an unexpected error and your recent changes to Dissertation.docx may have been lost. Playback error—sorry about that. :/ By the way, this road is under construction. Have you checked your spam filter?)

If you use any more complicated bit of software, you’re likely to find soon that the comforting sense of knowing what you’re doing evaporates, and you’re left with the harsh realization that even though a team of software engineers has spent several years building and refining this program for you, you still basically need to learn how to code in order to use the program. And even then you spend half your time just getting errors. Last year I tried to learn a 3D modeling program so I could make a simple animation of a metal strip bending. After three weeks I had succeeded in making a wobbly rectangular prism that sometimes stayed put instead of falling through the ground.

Words that one might use to describe the computerized technosphere if one hasn’t dug into it very deeply are: Convenient. Fast. Simplifies life. Opens new horizons. Words I would use after just a few years dealing with its other end: Rickety. Swiss cheese. Incomprehensible. Miraculous that it works. Or to quote Peter Welch’s “Programming Sucks”:

Websites that are glorified shopping carts with maybe three dynamic pages are maintained by teams of people around the clock, because the truth is everything is breaking all the time, everywhere, for everyone. Right now someone who works for Facebook is getting tens of thousands of error messages and frantically trying to find the problem before the whole charade collapses. There’s a team at a Google office that hasn’t slept in three days. Somewhere there’s a database programmer surrounded by empty Mountain Dew bottles whose husband thinks she’s dead. And if these people stop, the world burns. Most people don’t even know what sysadmins do, but trust me, if they all took a lunch break at the same time they wouldn’t make it to the deli before you ran out of bullets protecting your canned goods from roving bands of mutants.

And now they tell us that we should all start using the Cloud.1 Trust us. What could possibly go wrong?

Actually, that’s not precisely true. No one told you to move your life onto the Cloud. No vacuum cleaner salesman with the gift of gab ever showed up on your doorstep and told you about how much better life is when you live on the Cloud. It just kind of happened. Once, you had photo albums in your house. Then, one day, you woke up to find that when you wanted to look at photos of your life, instead of opening up a book that’s in a cabinet nearby, you were opening a computer, wading through a torrent of notifications bidding for your distraction, clicking to request information from computers owned by Facebook in unknown distant locations, and receiving your photos through the air. Something similar happened to your old collection of CDs (or vinyls, or mp3s, or cassettes, or all of them). Who needs all those when you have Pandora or YouTube, which you can get anytime, provided you’re connecting okay to the internet right now (and when would anyone be offline in the Year of Our Lord 2017)?

Why did we change this way? Well, because we can do more, of course. On Facebook there’s not just your photos, there are also the photos of all your friends. On YouTube there’s your music (provided it’s popular enough and isn’t the Beatles), but then there’s also all this other music you’ve never heard of, and some of it might be good, and it’s all free, not counting the ads.

Around this part of examining the internet is when we get to the crux of this point I’m trying to make. The question I’ve been asking myself lately is: Is it worth it?

Is the benefit of Facebook’s photo sharing worth the psychological shrapnel you have to withstand in order to use it, plus the price of knowing that in order to access your memories and your friends you always need the internet?

Be sure, also, to account in your calculation for the intricately interconnected infrastructure that brings you the things you want to look at. And the tendency of companies like Facebook and Google—companies that treat information on humans’ lives as a product they can buy and sell—to abruptly decide that you can’t do something you’re used to doing.

With that in mind compare Facebook to the old way: a combination of physical photo albums that you can sit down and tell someone about, plus writing individual letters or *ahem* thoughtful blog posts, plus the occasional phone call to “chat” with someone. Facebook wins hands-down on the score of convenience, because it’s all there in one place. But which one leaves you feeling like you’ve made a real connection with someone, and which one leaves you feeling empty and full of craving and longing?

I’ve been making this calculation with some of the Cloud-based internet things that I’ve used, and I’ve been coming more and more to the conclusion that it’s not worth it. That it’s time to back the hell away and take back some large swaths of my life that I’d entrusted to the internet.

You may have heard that I’m ditching Facebook. I’m also planning on printing out a bunch of my photos. And wherever I’ve got data stored on the internet, I’m copying it down to my own lowly physical hard drive, which is located not in the Cloud but right here on Earth, specifically in my room where I can keep an eye on it. I’ve long since abandoned Windows 10 and its slew of built-in spyware in favor of Linux, which tells you what it’s doing and doesn’t send your voice recognition data (a euphemism for “everything you say in its vicinity”) off to a multinational megabusiness.

And it’s in this same spirit—to finally answer the question I implied in the title—that I reprogrammed this blog.

That, of course, doesn’t make much sense if you don’t know how the old system worked or how the new one does. So I’ll sum those up briefly.

Blogger, which I just moved away from, is a service run by Google. To write a post I would log on, type a bunch of words, and press a big “Publish” button. In the course of that I might also upload some photos. Once the photos were uploaded and the post was published, I had no idea where they were kept. Basically, they went into a black box kept in an undisclosed location by Google, and I was allowed to peer in through the keyhole by typing in the right address. If I wanted to do anything with my posts besides show them on my single Blogger site, my only options were to either copy-paste them individually from the site (which is error-prone, like photocopying a photocopy), or download a huge text file with all the information I ever gave to Blogger wrapped into a bristling, unfriendly package. After 12 years blogging, the file is so massive that it chokes most text editors; it also doesn’t have line breaks anywhere, and even when you pick through the reams of cryptic metadata at the beginning of the file to find an actual post, it looks like this:

<entry xmlns="http://www.w3.org/2005/Atom"><id>tag:blogger.com,1999:blog-8044648.post-1084543713010246979</id><published>2016-11-20T01:20:00.001-06:00</published><updated>2016-11-21T10:33:12.306-06:00</updated><category scheme="http://schemas.google.com/g/2005#kind" term="http://schemas.google.com/blogger/2008/kind#post"/><title type="text">The Awful President America Needed</title><content type="html"><div dir="ltr" style="text-align: left;" trbidi="on"><i>(I hope you guys like ten-page essays. That seems to be all I’m capable of writing these days.)</i> <br /><br />So: Trump, huh?<br />&nbsp; &nbsp;You’ve probably noticed, but [... (full post text) ...] I’ll let you know what I’m going to do. And then we’ll both <i>do it.</i><br /><br /></div></content><link rel="replies" type="application/atom+xml" href="https://chuckmasterson.blogspot.com/feeds/1084543713010246979/comments/default" title="Post Comments"/><link rel="replies" type="text/html" href="https://www.blogger.com/comment.g?blogID=8044648&postID=1084543713010246979&isPopup=true" title="2 Comments"/><link rel="edit" type="application/atom+xml" href="https://www.blogger.com/feeds/8044648/posts/default/1084543713010246979"/><link rel="self" type="application/atom+xml" href="https://www.blogger.com/feeds/8044648/posts/default/1084543713010246979"/><link rel="alternate" type="text/html" href="http://chuckmasterson.blogspot.com/2016/11/the-awful-president-america-needed.html" title="The Awful President America Needed"/><author><name>Chuck</name><uri>https://www.blogger.com/profile/03918675492238901083</uri><email>noreply@blogger.com</email><gd:image xmlns:gd="http://schemas.google.com/g/2005" rel="http://schemas.google.com/g/2005#thumbnail" width="35" height="35" src="//lh3.googleusercontent.com/zFdxGE77vvD2w5xHy6jkVuElKv-U9_9qLkRYK8OnbDeJPtjSZ82UPq5w6hJ-SA=s35"/></author><thr:total xmlns:thr="http://purl.org/syndication/thread/1.0">2</thr:total></entry>

(By the way, that’s what XML looks like. If you ever see it mentioned, now you know.)

And if I wanted to find out where any single post “lived”, I got the same answer: we’re not telling you, but here, have this XML dump. It was similar with photos. I had to do some deep sleuthing before I even found where Google kept them. They’re not, as you might imagine, on the Photos area of my Google account with the rest of my photos. They were there, the last time I checked. But now they’ve been moved to an invisible zone dedicated to Blogger uploads, and you can only find it through clicking around in your blog’s backend. I was almost astonished to find that Google had deigned to include a button I could click to download all my blog photos in one big folder.

One last thing about Blogger: Google doesn’t care about Blogger. It has the distinct scent of abandonware. Blogspot was the hot new thing when Google bought it in 2003 and rebranded it as its own; everyone was using their Xanga or their LiveJournal or their GeoCities. Now, with the help of Facebook and (via YouTube) Google, the internet’s citizenry has been trained to care only about pictures and videos, not text, and Blogger is a burden from Google’s younger days that they still have to carry around. You get the feeling that the team in charge of maintaining Blogger has been reduced to a couple of guys at a card table in a basement of the Googleplex, while the rest of the company would prefer to imagine that it no longer exists. Since they reorganized as a subsidiary of Alphabet, Google’s been busy redesigning all their stuff to look sleek and modern. As far as I know, Blogger was their very last site to get that treatment, and when it finally came, it was full of misalignments and ugliness on the less-popular pages of the interface, which still haven’t been fixed. Blogger blogs are so ubiquitous that spambots know them and love them, and as a result Google has put its strictest spam prevention on these blogs—with the result that real people find it difficult to successfully comment on a blog, and might lose hundreds of words by submitting unsuccessfully. About this problem Google appears to care not one whit. It would surprise me only a little to hear an announcement sometime in the next few years that Google is shutting Blogger down and everyone’s going to have to figure out somewhere else to move to. That’s the sort of thing Google does.

Jekyll is the name of the new system I’m using. Jekyll isn’t a thing you log on to online; it’s actually a program you download and run on your computer. Its sole purpose is to take a folder with a bunch of text files and do a little processing on it to turn it into a blog. The blog it makes is also just a folder with a bunch of text files; the difference is that they’re text files that make more sense to Firefox or Chrome, and have the right decorations and menus included. You can toss them up anywhere that’ll host them. (I use a site called GitHub that makes it extra-easy.)

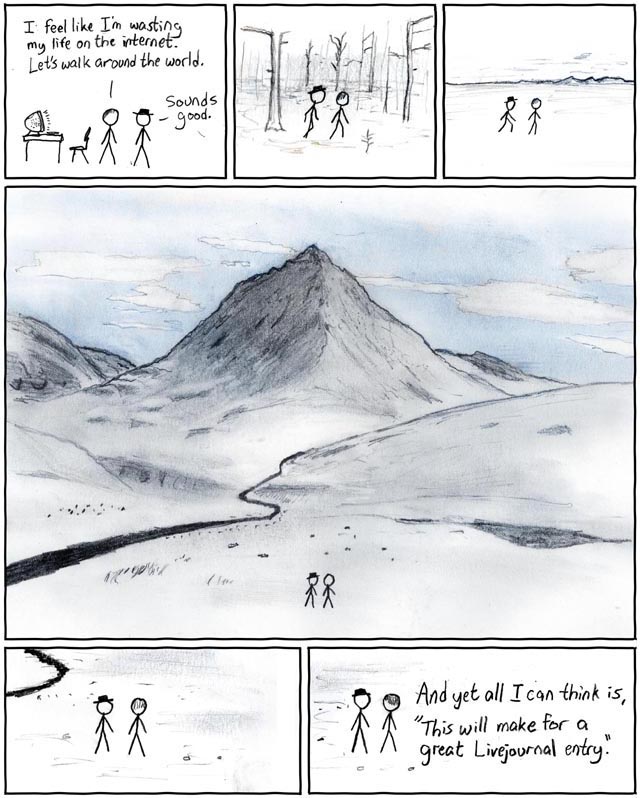

xkcd comic #77 (March 17, 2006)

And that simplicity is an important difference between a Jekyll blog (a “static site”) and most of the other blogs and websites on the internet. Most sites these days are ephemeral and immaterial in a surprising way: the pages that you go to don’t really exist until you go to them. Until you tell your computer to open up “www.xkcd.com/77”, that page isn’t all in one place anywhere. It exists as some entries in a database. What you’re doing is dialing up “xkcd.com”, and when you ask the computer on the other end of the line for “/77” it very quickly asks its friend the database for the stuff it’s supposed to show you, then assembles the page right then and there and sends it to you, then probably forgets everything it just built as a matter of course.2 There’s nothing sitting there waiting for you. It’s all built by machines scrambling like mad to get the page built in a just-in-time sort of way, and those machines have to always be working or you get nothing.

What that boils down to is that, if you have a site that’s like most sites, and it isn’t connected to the internet and up and running, it doesn’t really exist. I wanted my blog to exist. Jekyll was the answer.

Once I run Jekyll I can, if I want, look at and change a copy of my blog even if I’m off the grid and there’s no internet around for miles. I can also pack up the whole website onto a flash drive. Or I can run some program that turns all the posts into a printable book. The point is, I have the blog. I have my data. It’s just a bunch of simple files on my computer that look like this—

---

title: "Changing My Blog to Jekyll: *Why* I Did It"

subtitle: |

*or,* Getting Right with Technology.\\

(For those who don't code.)

categories:

- meta

- technology

---

*This is the first of two posts about redoing my blog, although the

other one will be aimed at a different audience, mostly consisting of

programmers trying to do the same thing I did.*

{: .prefatory }

*I’m aware that I promised to write about sugarbush. My time there

turned out not to be a solid week but several discontinuous days, and

I haven’t yet spent all the time I’m planning to spend there. I’ll write

when I have, but meanwhile I’ve been wanting to write this.*

{: .prefatory }

I'm going to take on a bit of a challenge: I’m going to try to make some

very nerdy programming stuff interesting to regular people, people who

have no interest in code other than that it should work---even people

who fear code and want nothing to do with it. [...]

—and the Cloud can bugger off.3

I like to think of it as “a blog to outlast the internet.” The internet is unstable. Each year some old services die or become unusably buggy, and a crop of new upstarts sprouts up. Even though Jekyll is a thoroughly modern project and this blog uses some pieces that are even more modern than Jekyll, I’ve got fallbacks for all of them: a series of fallbacks that go from “commenting is inconvenient” to “here’s a nicely-printed book of some things I wrote on the internet back when there was an internet”.

Which is why I spent all that time coding. I learned to use this technology because I’m suspicious of technology. I reined in my technological use from something that’s easy but complex and inscrutable to something that’s somewhat more difficult but simpler and doesn’t hide anything from me. It’s a bit like switching from driving to biking. There are some limitations that I have to accept, but now I know how to fix the bike (and soup it up) at home with simple tools, because I can see all its moving parts. And since I’m no longer dependent on Google for gas, I can ride as far as I want and wherever I want.

It took a lot of effort—it’s never easy to get something into a state of lower entropy—but I’m glad to have done it before moving off the grid. Now I can write on my own terms. It’s a load off my mind: one more string of dependence severed between me and the collective cybersphere of the world.

If you’ve read this far and you’re bemused and it all seems a bit irrelevant, just consider what you’re depending on without thinking about your dependence. What if that thing you’re depending on were to vanish? It wouldn’t even take the death of the internet—which could be many decades in the making—to bring some serious disruptions. Just one site could go down. Or even something that’s not the internet: your car, for instance.

I’m going out to the land to find the old human memories of how to live without these things. No one is completely self-reliant in this world, but I’d rather rely on people I know than technologies I don’t. If you expect the things you depend on to always be there, then I suppose there’s no reason to learn to do without them. But the more complex something is, the more failure-prone, and a lot of the systems we depend upon these days are just staggeringly complex. I used to ignore that fact. I don’t anymore.

-

One of the more brilliant extensions you can add to your browser is “Cloud to Butt”, which searches news articles you’re reading for any mention of “the Cloud” and replaces them with mentions of “my butt”. Please feel free to imagine this has been applied through the rest of this post. ↩

-

Actually, the workings of xkcd might be much more mysterious and subtle. It’s run by an extremely nerdy guy who’s probably done some extremely nerdy things with it. ↩

-

“And my butt can bugger off.” ↩

File under: meta, technology

Note: comments are temporarily disabled because Google’s spam-blocking software cannot withstand spammers’ resolve.

9 Comments

Cicada

HistoryThis is all great news! My internet use, disuse, and avoidance bug me at least once a week, and I too want to move offline. Now I’m just glad I don’t have a 12 year old blog to deal with…. Just thousands of photos I may or may not want to save a physical copy of.

Chuck

HistoryI have a similar love/hate relationship with the internet, I think. Maybe I can eventually get my use down to just this blog and the emails that go with it.

By the way, if the photos are on Facebook, I’m pretty sure it’ll allow you to download a copy of all your data? I don’t know what that copy looks like or if it’s easy to use, but you should be able to get it.

KEITH NEEDHAM

HistoryGreat read. Very interesting perspective on Facebook, and how it impacts your life. Just remember to keep our notes in physical, paper form. :)

Chuck

HistoryOh, absolutely. They’re safe in a binder in a box in the basement.

Dave

HistoryWell, I have a few observations. The first and foremost- why anyone still uses Facebook is beyond me. I’ve never seen anything good happen because of Facebook. It certainly is the lowest hanging fruit on the tree of internet addictions. When I ‘took my data back’ from Facewaste, I had to ‘schedule my account for deletion’, which was a date no sooner than a full two weeks in the future. I’m convinced it’s still out there. Somewhere. Anywhere. If I had the urge to fall off the wagon, I’m sure some codester at Wastebook could extract it from their equivalent to Area 51.

Yes google doesn’t care about internet posterity, but the shares I bought last year for $725/share are now at $850, so that’s full of win. Someday I’ll cash out and buy a cabin on a lake. I won’t be off the grid, but my cellphone will be at the bottom of the lake, it’s a recurring dream that will come true someday.

I hope this creaky code you’re talking about is better in airplanes, my latest ride is fly by wire. No electric mechanical backup. Just ones, zeroes and a joystick. All fly by wire airplanes have backups. I have lots of electrical sources: three generators, four batteries, and a ram air turbine emergency generator. If my fly by wire code is corrupted, there is a second system, standing by, ready to take over. The second system doesn’t talk to the first system and is written in a different computer language or perhaps it’s a code. It’s PFM(pure f*cking magic) to us Luddites up front, but it hasn’t failed yet! It is newer, better and safer than the old junk that was around when people blogged. Ha!

Chuck

HistoryThe code’s probably better in airplanes, I’ll grant that. There are people testing that stuff really well. And having several independent fallbacks is what I would hope they’re doing.

Cell phone at the bottom of a lake… now there’s something to make some people’s hearts sing and others’ convulse. Sounds pretty nice to me, except I’d probably dispose of the most toxic bits elsewhere. Oh, wait, all of it is pretty toxic. Guess it’d probably end up at a recycling center, but I could definitely throw in an effigy with you someday.

The Draw only has a landline, for what it’s worth, and there’s barely reception if you do bring a cell, or so I’ve heard… though I’ve always turned mine off as soon as I go through the gate.

Chuck

HistoryOh, but I remember now, I was going to mention: Have you been keeping up on the latest on the F-35? It seems to be run by software so advanced that not even the plane understands it! It’s just cost overrun after bug after failure, at a cost of countless billions.

VERNE TROXEL

HistoryI find it all fun so I will keep it all. Sorry your leaving us but ye shall be what ye shall be. My view is different than yours therefore ‘HASTA LA VISTA, BABY” oh wait a minute, someone already used that line. See ya at the Duck in future years if I can contact you. Oh yeah, I haven’t a clue what you were talking about. G.Pa

Chuck

HistoryWell, I’m not leaving you. I’m leaving a particular way of contacting you, one that I barely use these days anyhow. I will indeed see ya at the Duck, though.