Camp Turtle Island

or, Perhaps the Future's on the Rez

About twelve miles east of Waubun, Highway 4 comes off of Highway 113 and heads up toward Nay-Tah-Waush. There at the corner, there’s something unusual going on. Down in the grass there’s a scattering of tipis, two huge army tents, and a trailer, spread among a selection of cars ranging from serviceable to dead and an uneven layer of debris like chainsaws, old doors, and cinder blocks. Come down off the road and go down the hill toward the nearby banks of Gull Lake, and the theme holds and intensifies, with a half-dozen wigwams lining the trail, some covered with layers of tarps, some no more than a dome-shaped frame of bent saplings, flanking a yard full of old boards, scrap wire, insulation, a blue ’60s flatbed dually. Facing toward the road is a big banner that says

MikinaakMinis

Camp Turtle Island

What’s going on here?

I should start by explaining where we are. We’re on the rez. Although you could be forgiven for not noticing, since the White Earth Band of Minnesota Chippewa own only nine percent of the land within the borders of their reservation—which explains all the cornfields and that little gas station full of white guys talking about deer hunting. Your only clue would’ve been up north of Waubun in Mahnomen, where the casino sits, full of gamblers from Fargo and Winnipeg, and locals gamely feeding their percap back into the tribal coffers. It’s the rez, but it’s also Minnesota—outstate Minnesota, way outstate, where the bright nighttime lights of the Twin Cities are a distant and hazy notion, and people white and Native alike say “Ish!” to something gross and “Oh for nice” when they’re pleased, and the highways wind erratically around lakes splashed across the map.

These twenty-four acres on Gull Lake are Bill Paulson’s land, and they’re where he’s putting together Camp Turtle Island. Turtle Island is, in origin, the sprout of one of the many seeds that blew away on the wind when the camps at Standing Rock were evicted and burnt down at the end of 2016. If you were there, or if you saw pictures, Turtle Island may look familiar to you, except writ much smaller.

Standing Rock had, at its peak, three or four thousand people from at least three hundred different tribes from every part of North America, as well as tribeless colonists’ descendants. At first there were just a few local Dakota from the Standing Rock Reservation who saw that the under-construction Dakota Access Pipeline was planned to carry dirty crude under the Missouri River just upstream of their drinking water source, decided this was one shitting-upon too many, and put up tents where the bulldozers would be heading next. In the ensuing months, Standing Rock turned into a pressure point, and Native people from all over the continent joined the camp, building not just a tent shantytown but a functioning community with traditional healers to care for the wounded and sick, a council of elders to advise the people’s decisions, a warrior encampment, and even a school for all the kids who’d wound up there.

It was the biggest gathering of the tribes in, well, ever, and it was the closest thing to a traditional Native village that’s been seen outside a historical re-enactment in a century or more. Yes, there were electrical generators around, and cars, and canned food coming in through donations, none of which was around before colonization—but culturally, people were relying on each other, finding self-determination, not answering to the Great White Father in Washington, getting together to teach and pass on old skills. It started out as a gathering for protecting the water, and it never stopped being about that, but by the end it was about something much bigger as well: it was about being able to live. Imagine that for your entire life, and for the lives of all your ancestors for a century or two, if someone asked, “Where do you see yourself in five years?” the only response you could muster was a hunted look. That’s the situation a lot of Native America has been in since Sitting Bull’s days. Standing Rock was about people being able to catch a glimpse of a future for themselves for the first time. And when the eviction came due and the riot police bore down, chasing the people out of their own unceded land, the victory songs that the people sang weren’t just stubborn reality-denial, they were notice that although they had lost the battle over the Missouri River, they had transformed in the process, come alive. As the proverb goes, “They tried to bury us—they didn’t know we were seeds.”1

So far there have been a number of tentative sprouts of those seeds, though for most of them it’s too early to tell if they’ve fallen on barren ground or fertile soil. Camp Turtle Island, in any case, is one of them, and while Standing Rock had thousands, Turtle Island so far is basically Bill Paulson plus a rotating cast of wanderers who’ve found their way there over the two years it’s been in operation. When I arrived in late October, the carefree summer was over and the cold season was setting in, and accordingly there were only two other people besides Bill and me—Jason and Carol, young and in love, though the kind of love that involves constantly loudly making fun of each other, punctuated by occasional tenderness.

Bill is fifty-seven and has a mustache that brings to mind Frank Zappa. I only saw him without a baseball cap once or twice; he particularly treasures his pink one. You wouldn’t pick him out of a crowd and say, “Hey, that guy’s Native,” but while at one-quarter he may be at the low end of the famously useless measure of blood quantum, he’s Anishinaabe bred-in-the-bone, having been raised on White Earth by a father who was born in 1908 and taught him all the old traditions he could learn, both the physical and the spiritual aspects of them, besides teaching him how to run a farm that stays afloat, fix everything that can be fixed, and keep spare things around until the day they’re useful. Bill went on to refine those physical skills through a series of industrial, building, and farming jobs—“I top out at about three to five years at a job, and then I have to move on,” he says—and the spiritual ones through five years apprenticing to Earl, a Red Lake medicine man, living in his basement and getting his sweat lodges ready for him (among the other tasks of an oshkaabewis).

Bill is also one of the great explainers. One day a visitor came up from Minneapolis, an older woman, city-raised and with very few notions of what Anishinaabe tradition was like, carrying the usual white-guilt anxiety about even asking questions. Bill spent an hour with her in the kitchen (while I listened), giving calm, cogent answers to questions ranging from “a culturally raised kindergartener would know this” up to thought-provoking adult ones. The next day he took her and me out to see his sweat lodge and explained about how he chose the site and built it. He’s not content to just have knowledge, he wants to spread it to everyone.

I came prepared to fight for the water. After all, the term “water protector” gained its fame at Standing Rock, and Bill’s notion to build this camp was inspired both spiritually and organizationally by his nine visits to Standing Rock. And a fight I found. Enbridge’s Line 3 pipeline, on its way from Winnipeg to Duluth, is slated to skirt around the corner of White Earth, only seventeen miles from camp, and go down south between White Earth and Leech Lake Reservations, avoiding both so as to despoil land mostly owned by non-Natives, who won’t put up as much of a legal fuss. The proposed Line 3 is actually a replacement for an aging pipeline of the same name, though with a somewhat different route, cutting straight through Leech Lake.

Any way you slice it, this is a bad pipeline. The proposed route for Line 3 crosses the Mississippi fully three times, only miles from its source in Lake Itasca, not to mention the trenches and rights-of-way it would chew through forest that surrounds some of the cleanest and most precious lakes in Minnesota. Bill informs me that Gull Lake has been tested so clean that there isn’t even a mercury advisory on its fish. Further on, the pipeline would pass within a few miles of the place where, earlier this year, I drank delicious mossy-tasting water straight out of the Pine River for a whole week and never got beaver fever or even an upset stomach. Wild rice, the staple food of the Anishinaabeg,2 needs uncontaminated water to grow, and if the pipeline gets built, then when the oil spills, as it inevitably will, it may (depending on location) destroy the ricing and cripple the fishing for the people of two reservations or more, plus surrounding towns. The proposal also includes plans for abandoning the old Line 3 right where it sits, without pulling out the oily pipes, just letting them sit and corrode, ecological time bombs.

So Bill’s focused on stopping Line 3. He’s testified in front of the Public Utility Commission (testimony that, along with the other ninety-some percent of public feedback that opposed the line, was roundly ignored), he’s blockaded a road in Bemidji, and he’s planning legal and other offenses against the construction if and when there’s any construction to attack. (For the moment, it’s held up by more permitting.) But here’s what makes his camp special. Bill has grasped what the vast sweeping majority of the environmental movement on this continent has failed to figure out: that in order to keep the Earth from getting destroyed, you can’t just tell other people to stop destroying it, you have to start by not destroying it yourself.

That first tack is really what most environmental activism boils down to, after all. A grandiose rally in Washington such as I attended in 2013 amounts to waving around signs that say “No” and “Everyone else fix this problem”. Now of course it does seem to make some sense to tell people who are destroying nature to stop destroying nature. But we’ve been trying that since at least the 1960s and the success has been, well, pretty limited, judging from all the stuff we keep hearing from the IPCC and concerned scientists worldwide. We’ve got some national parks and such. That’ll keep ’em quiet, say the destroyers, and go on destroying.

To get anywhere, you have to go at least a level deeper. Why are the destroyers destroying? Well, because we fucking pay them to! Do oil companies send trucks to our driveways and blockade us in with barrels of gasoline, keeping us from leaving our houses until we burn it all? No, we voluntarily give large chunks of our paychecks to oil companies. If I were an Exxon exec, I think I would find it deeply amusing to watch a crowd of people protest my supplier’s pipeline, and then all stop their cars on the way home at my nearby gas station and contribute thousands of dollars to me so I could help my supplier pay for all the time his construction workers just sat idle. You see how there’s something deeply dissonant going on.

Objection! The environmental movement has known for years that it’s important to watch where you spend, and its leaders have relentlessly encouraged its supporters to “vote with your dollar” and “buy local”.

Overruled. The supporters you mention, and the leaders alike, have overwhelmingly stopped at token gestures like changing their light bulbs and buying hybrid cars. They still take airplanes for their vacations, drive half-hour or hourlong commutes, buy their phones smart and new, and consume massive quantities of resource-intensive foods, howbeit organic and free-range. People who do more, in this country, are harder to find than monks who wear hairshirts.

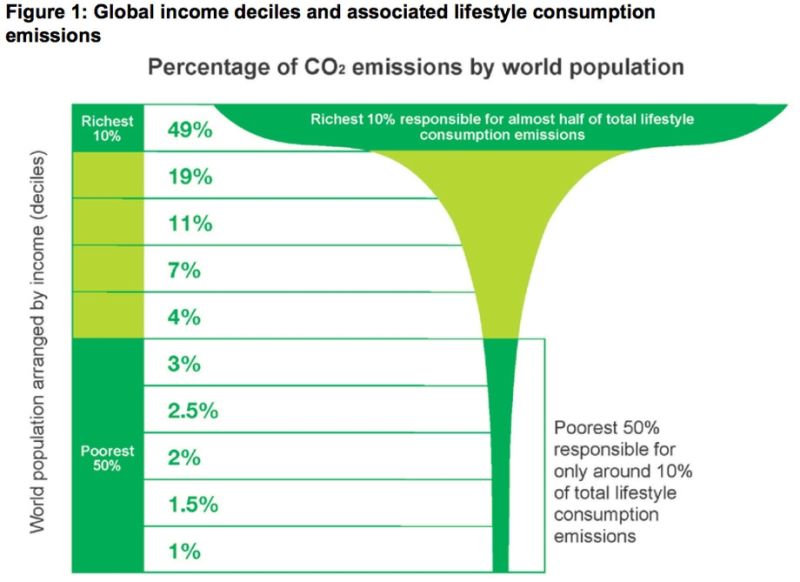

A visual aid might be useful:

If you live in the US or western Europe, you are probably in that top green bracket. If we’re going to get down onto the stem of the martini glass, as we must eventually whether voluntarily or no, we have to accept that our way of life is going to change, a lot. We’re going to have to stop asking questions like, “Which manufacturer makes the best solar panels for charging my electric car’s battery?”3 and start asking ones like, “Who sells good refurbished old bicycles around here?”

Those kinds of questions are Bill Paulson’s bread and butter, or I suppose his wild rice and bear grease. Bill isn’t the first person to move towards living a post-petroleum life. But several of the things he’s doing are making me begin to suspect that Camp Turtle Island is the future. I should specify that the future I’m talking about is the one I’ve talked about on this blog before, the kind of future I expect us to get: not one of colonizing the stars, a misguided dream that’s currently dying a messy death, but one where we reckon with the consequences of our and our ancestors’ profligacy, in the form of resource scarcities and a wounded planet. Why do I think he’s on to something?

For one, while back-to-the-landers in the grand tradition kicked off by the Nearings and ratified by the hippies may have their heads in the right place, their hearts seldom are. A hippie couple might reject all the trappings of modern life and go build a tinyhouse on forty acres where they grow their own food, and they may be very successful with their harvests. But look at their culture. They have none; they swept it all into the trash can when they abandoned the city. They probably reject Christmas as a consumerist orgy, and believe climbing a corporate ladder is a pointless exercise likely only to twist your mind. But these positions, while justified, are absences only. What fills the hole where those bad old traditions have been jettisoned? Nothing, so far; the holes are still open, and yet humans need traditions in life, need to feel a connection with something larger, can’t live long if they feel they’re free-floating with no guideposts. We need a model of a virtuous life. And unfortunately for those who want to start over afresh, it takes more than one couple or one ecovillage to create a culture. It takes villages’ worth of people hundreds of years to settle into a functioning idea of what we should shoot for with this life we have.

The US’s culture is in the process of having a crater blasted in it, as its central narrative, “The world is just going to keep getting better until humanity arrives at its ultimate destiny,” is empirically proven false. A new culture will arise in time, as people borrow and invent bits of worldview to fill in the giant hole. Meanwhile, though, it’s interesting to note that an Anishinaabe elder said, “We aren’t losing our language. Our language is losing us.”4 The same could be said of Anishinaabe culture. The ideas themselves haven’t died as the US’s have, they just haven’t been able to find enough people to carry them from generation to generation. And Bill Paulson aims to bring that culture to as many people as he can teach it to at Camp Turtle Island.

It’ll be a cultural camp, he explains, once the infrastructure is in place for it. What does that mean? It’ll be a place where people can come to learn about Anishinaabe lifeways by living them. He’s already been teaching wild rice harvesting for years. He’ll be expanding that to teach the whole yearly round of the seasons, from sugarbush to gathering fruit to ricing to hunting to icefishing and back around again. He’ll teach wigwam-building (already has), medicines he learned from his mentor, and stories, and he’ll hold sweat lodges. He won’t have to search hard to find the time, because this is already how he lives. He eats food from stores, but a sizeable chunk of his diet comes from the hunting and gathering he does. One day he showed me and Jason how to skin beavers, and later that week we ate beaver meat stew. He trades, too—while I was there he brought an eight-pound cylinder of gouda in, and told me it came from an Amish guy he knows about two and a half hours away. “My barter network stretches pretty far,” he said.

A culture doesn’t exist without a community, and Bill is a big part of White Earth’s. Specifically, he’s sort of the go-to fix-it guy—people are always coming by asking him if they can buy some used tires from him, if he has such-and-so car part, if they can use his trailer to move house. Bill is constantly giving to the community, and the plans for the camp are to just keep on giving: he plans to start up an art stand where local craftspeople can sell their bone carvings, their quillwork, their screenprinted T-shirts, their jewelry, anything they make, because outside of powwows there isn’t a place for that on White Earth yet.

Art being as important as it is in culture, in fact, one of the central things in the long-term vision for Camp Turtle Island is to have a sort of folk school set up, where craftspeople from all around Indian Country can come and teach their art—weekend courses, weeklong ones; the North House Folk School has shown it can work, and this would be similar but with a focus on Anishinaabe crafts. Imagine a place you could come to learn how to build a birchbark canoe, learn beading, or even get immersed in the Anishinaabe language. Even if that’s not your particular cup of tea, you can see how it’s exciting, for the teachers and the learners both.

So, having a living culture to draw on makes a huge difference, and could make Camp Turtle Island a place people come to learn for years and years as the world changes and these skills become more obviously useful. But another thing that makes it different is this: Bill is an expert at creative solutions, and that means he doesn’t need to rely on money nearly as much as he might otherwise. It’s all well and good to start a project like this if you can have someone bankroll the startup costs and make ongoing contributions. But if you want it to be sustainable, plan on it being self-sustaining. Now Bill, when faced this summer with the need to house over twenty people, didn’t run off and buy another giant army tent at a cost of a few grand, or start building frame houses. He started harvesting ironwood trees and teaching people how to build wigwams—and ended up with the small flock of them that line the path down the hill. When he needs a woodstove, he doesn’t go out and buy a new one, he finds a metal vegetable oil drum for twenty bucks and a barrel stove kit for thirty, and makes his own. He’s gotten grants, but Bill is constitutionally suspicious of free money, and prefers to fend for himself. He’s well capable.

My biggest project while I was at camp was to build a platform for a yurt to keep it from getting water-damaged once it’s set up. I put the whole thing together from Bill’s woodpile, which he stocked when an old powwow grounds was getting replaced and when a town hall for a defunct town was torn down. The boards even came with nails in them, and after he taught me an easy way to straighten them, I hardly needed any new ones.5 That’s something that makes me think he’s on the leading edge of a big wave coming: the ability to use everything you can find. The pre-colonial Anishinaabe didn’t make all their stuff out of natural materials because it was natural, they did it because that was all there was to build with. And they were geniuses at it. They invented buckets;6 they made them out of nothing but birch bark sewn with cordage and sealed with pine pitch. They built canoes that were so fast the French voyageurs copied them point for point. Putting together the material things of your life today with minimal money to spend on it is a similar task—you look for what can be gotten cheap, and you MacGyver it together into something. This is a skill that’s going to be more and more important on the downslope. New materials will get scarce, but salvage will be plentiful for a century or two, and using it will get you an edge over anyone who doesn’t. No sense being purist, the stuff’s out there, just make good use of it. Communities of the future will probably look like hilarious mishmashes of things from all different time periods mostly not being used for their intended purposes.7 Camp Turtle Island already has something of that air; well, as William Gibson says, “The future is already here—it’s just not evenly distributed.” On an upswing, you can expect the future to arrive first in the cities and the centers of power. On a downswing such as we face, you should look instead to the hinterlands, where the wave will recede first.

It was at the end of a long stretch of wandering that I found Camp Turtle Island, and one of the goals of that vagabonding was always to find the place I would settle down when it was over. These considerations I’ve been writing about have made me add Turtle Island into the running for a place I could end up living—bringing the total to two: a part of my heart is also still drawn to the Chequamegon Bay, the last place I was in, where I’ve made friends and memories. Before I went to Turtle Island my decision was so much easier. But I can’t deny that if I stayed there—and Bill has told me there’s room for people who’d stay and help the place run—I would have the opportunity to learn things I’ve always wanted to learn, just in the course of daily life, whereas if I could find the same opportunities on the Chequamegon they would likely be fewer and farther between and I’d have to go out of my way to get to them.

At the same time, I can’t give Turtle Island categorical approval either. Because whatever impression I may have given here, it’s not perfect, and it’s too soon to tell yet whether the place will actually turn into the amazing project of Bill’s dreams, or struggle to make it out of its junkyard phase. For one thing, I haven’t seen much indication that anyone but Bill will see the project through. He’s handed over the reins of the camp at least twice to people who came to help and told him they’d help him run it: Bill is only too happy to give some of the responsibility over, since running a camp is a complicated job. Each time, the person who took over crashed and burned in the end. At some point in the summer there were dozens of people at camp, but when I arrived there were Jason and Carol (not counting Bill’s wife Teresa, whose time is taken up by a cat rescue business that has her caring for over a hundred cats, and his daughter, who mostly helps Teresa). Why don’t people stay?

One possible answer divides the world into two kinds of people: wanderers and those who are stable. Wanderers, of course, are the ones most likely to find Camp Turtle Island, but the inability of the American wanderer to stay in one place is well-known. Meanwhile those with a house who might be interested either never hear of Turtle Island, or are spending all their time keeping the house out of the clutches of their creditors and can’t spare the time. What kind of people would stay? People from White Earth who want to help? The odd wanderer like me who is looking to settle down eventually? It’s hard to see; this belongs to the future. But if the crew is always going to be skeletal, how far will the place get? Bill may be a mad genius, but he’s only human, and he needs help. If I came, would more join me, or would I spend a year getting frustrated and then wash out myself?

Would the right kind of people come? Wanderers often wander because they’re trying to run from problems that they’re unwittingly carrying with them. We had a vivid example of this toward the end of my stay, with the arrival of a guy who had been warped by eighteen years in prison, and whose thoughts now ran in circles, which came out in a constant spinning jabber that had the unnerving effect of grabbing onto everyone nearby and sucking them in like a snowball rolling downhill. Eventually the snowball guy proposed a mutiny, and nearly broke up the entire camp—Jason would’ve followed him, Carol would’ve refused to stay alone, and I was ready to leave too. Luckily we came to our senses when the snowball guy left, but it was a sobering experience. Drugs and alcohol aren’t allowed at camp, and it’s meant to be a space where people with drug problems can come to get right. But there are a lot of drug problems in rural areas, doubly so on the rez, and they aren’t always willing to depart from their hosts on the doorstep.

These are considerations, and I’m still considering them. The vision is there, and it’s what made me tell my old confidant Misty, on the evening I left for the holidays, that I may have found where I’m supposed to be. I don’t know yet whether it’s more information, more time, or just more daring that I need in order to make my decision. In the meantime, up at camp, I’ve missed a storytelling night, they may have put up the yurt on that platform I built, and I’m curious who’s weathering through the winter there in the warm army tent with the double barrel stove. Camp Turtle Island may be an answer to the predicaments of this moment in history; it may not be. What I know for sure is that it’s a good place, and White Earth, Minnesota, and the world are better off for its being there.

-

First written by Greek poet Dinos Christopoulos in the ’70s, and morphed into a proverb in the ’90s by the Zapatistas in Mexico. ↩

-

The -g makes it plural. ↩

-

Hint: you can’t afford enough panels to drive more than a few miles a week, and your property doesn’t have room for them if you could. ↩

-

Joe Auginaush in the introduction to Anton Treuer’s Living Our Language. ↩

-

Though not everyone takes to this like I did. He told me he was working on a project with a friend, and while they were straightening a dozen or two nails together, his friend suddenly put down the hammer and said, “Jesus Christ, Bill, can’t we do buy a fucking pound of nails?!” ↩

-

It’s called a makak (muh·kuck). ↩

-

I’m indebted once again to John Michael Greer, this time in his book The Ecotechnic Future, which outlines a future series of transitions from the current abundance industrialism to scarcity industrialism to salvage economy to ecotechnic society. ↩

File under: activism, Anishinaabe, land skills, new world · Places: Minnesota

Note: comments are temporarily disabled because Google’s spam-blocking software cannot withstand spammers’ resolve.

5 Comments

Dave

HistoryForm follows function, and humans follow the path of least resistance. We all have a thirst for something more, something outside of ourselves. For me, I found marathon running. It takes you to a place with yourself that few will ever get to. You find limits, break limits, anguish, euphoria, heartbreak, and pure joy, all in 26.2 miles. But after those few hours are over, I want a cold drink, warm meal, soft bed and climate controlled living space. We can’t live on the edge for more than a short period of time. To think that the world will voluntarily devolve, the way it eventually will is nothing more than a dream.

You’re pushing your boundaries and finding the edge, I think that’s great. But I don’t think you’ll ever find community living in this manner voluntarily. You’re anecdotal sampling over the various players seems to back that up. You’ve won a lottery ticket. You get to be a bombastic resource exploiter. All things have a cycle and we are stuck in the period we were born into. I think your visions of the future are correct. Someday in the future resources will be scant, and nobody will be living in space. If anything altruistic is happening, it is this- our energy hoarding lifestyle is certainly producing technological fruit that future generations won’t be able to produce. Perhaps the iPhone 20 and it’s associated technology will be seen as the equivalent of Greek philosophy or Roman law one day. Both were cultural high points that keep on giving to the future. Certainly we are producing similar fruit.

Chuck

HistoryI agree that people aren’t going to stop being profligate until they have to—that’s something I’ve been discovering during my travels. What’s interesting to me is places where they do have to. Wherever people are poor, because they’ve been locked out of the global game of money flow, you find that community starting to rebuild itself (if it ever disappeared). That’s what I see tentatively starting at Camp Turtle Island. They don’t have a lot of money on the rez; never have. So they have to work together to get by day to day.

I guess where the interesting part lies, to me, is that as time goes by, more and more people are going to need to know how to rely on each other rather than the big system—but they might not have any clue how to go about it until it’s almost too late for them, depending on how suddenly things change in their life situation. And ideas that are useful might get lost in the jarring transition, or not get spread from where they were invented to where they’re needed. So a way to do good in these times is to help people see what’s coming, know how to adapt to it, and spread their ideas among each other.

Kartwheel

HistorySuper stories and accounts, Nathanael. It’s great to hear from you! Sounds like a place that suits you well, and not without some of the difficulties of all places. Hobo level 5 (out of 5)? Is anywhere perfect? I think not… but when we let our paths (paves?, with a short A? nah just trying it out hehe) lead us, or our heart settle into where we are or are brought to, we accept the imperfections and decide to work towards the world/place/community we want to see. And a work in progress, always. (Practice for life. Chronic!! Terminal striving whilst perpectually letting go) Annnddd some folks say home is where the heart is, and wherever we go we carry the light of our selves and nestle into the present as if we’ve always been there (OK I just made up that last bit)… so whenever you or I or we or one goes, treat it as if it could be home… or not, and enjoy it and leave at the end of the day, thankful for fire or light or food or company. Contradicting and vague statements aside, miss ya and am glad to see what you’ve been up to. Thanks for sharing your experiences, giving us all a taste of what we miss and get through others. Much love- Kd (PS. I AM NOT A ROBOT… I am a bi-borg)

Chuck

HistoryYeah, maybe you could define perfection as the act of striving for perfection. Like the Tao Te Ching says, “The greatest perfection appears imperfect.” I think that’s why I’m leaning toward spending the rest of the winter there to see where it goes. If I give up on the place because no one stays, I’m part of the problem* because I didn’t stay, but if I give it a real try, try to let it be home, be part of the possibility of a solution and a future… something may come of it. And if it becomes clear it won’t, well, I probably wasn’t missing much in Ashland anyhow over the winter, and I can move there later.

Miss you too. Thanks for checking in, it’s nice to hear you, it’s like there’s a little sunny spot I can see all the way through the internet where you peeked in.

*Yogi Berra’s words seem strangely relevant—“Nobody goes there anymore, it’s too crowded.”

alfi

History“New materials will get scarce, but salvage will be plentiful for a century or two, and using it will get you an edge over anyone who doesn’t. No sense being purist, the stuff’s out there, just make good use of it”

I still remember you wrote something about post industralization before, didnt you? People invented many things which actually it create problem in the end. For Indonesian, back when we were Dutch East Hindia , people walk and ride a bike. But now, there is a survey that revealed Indonesian (mostly capital people) walk rarely in their daily life (Thats why then the goverment makes a car free day in some places every sunday). The logic works in another case too. Before, people didnt even touch the forest cause they believe supersition that something is there. Now we opened the forest, mostly for the palm plantation and it damages the orang utan and indigeneous ethnics. Even the goverment promotes sustainable palm oil industry but till today could not trust it. Banning palm oil will only increase the number of poor people, they said. And what most people are bragging a lot now? plastics in the ocean. Recently a whale was found death in one Indonesian’s beach with a belly full of plastics. While one local goverment ban the plastic usage , the association of plastic industry prosted it cause the gov should not ban it, instead they can promote people to use the degredable one. Decreasing the plastic usage will make people in plastic industry lose their job. Basically, if people choose traditional way, Indonesian society can use less plastic.. but again how bout life of people in the plastic industry?