Play Catch-up

A month and a half of back posts

Bottling up the season

The syruping season usually lasts about three weeks, from the first time it warms up enough for the sap to flow, until the tree starts turning all the sucrose in its sap into cellulose, which it uses to build leaves and begin spring. This year it lasted seven weeks. When I was planning, I figured I’d be there the entire time, because I had the whole month of March and a little of April to spare. But spring teased us week after week: we’d have a few days above 40°, and think, “Ah, good, as soon as this melts the snow, the roots will be warm enough to send up sap.” And then it’d go back down to highs of 31°. “Maybe next week.” Well, next week and next week brought the second coldest April on record in Minnesota. Canada geese, trumpeter swans, and sandhill cranes who had winged back up in mid-March with the breath of warm promise in the air were stuck flying around in circles, looking for something to eat in the snow or in the little patch of open water under the Independence Street bridge where a stream brought deep water up to the surface. I woke up on April Fools’ Day to 3½ inches of snow on my tent.

More snow came later in the week. We occasionally got a few gallons of sap, but by five weeks into sugarbush, we had boiled that into not even twenty gallons of syrup; last year we made seventy. More snow came in the next few days, and I realized I wouldn’t be able to stay until the end of the season. I’ve been working on going with the flow and letting life take me wherever it wants to, but even so, there was something I needed to take care of.1

A spot of bother

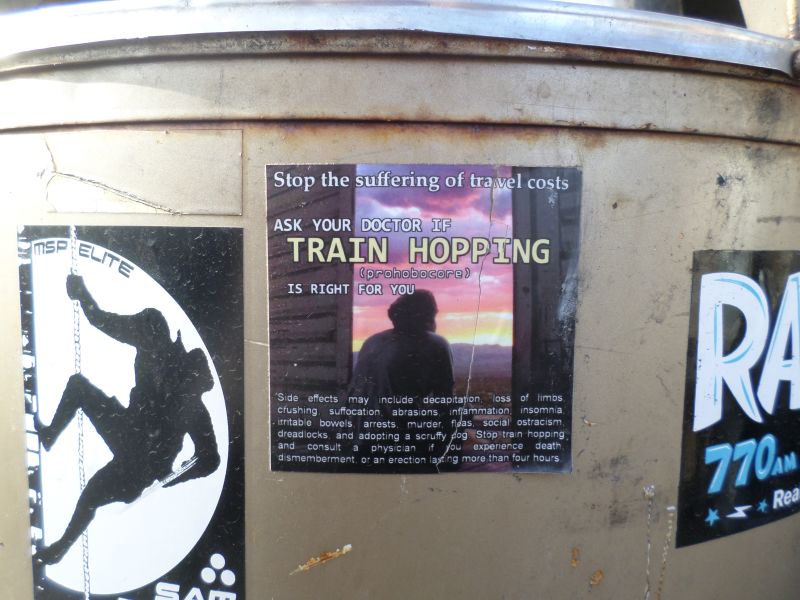

Back in October, on our way out to Portland, Misty and I rode fast trains down the High Line. It’s seventeen hundred miles of track from Minneapolis to either Seattle or Portland, depending on which way your train forks at Spokane (usually the wrong way, it seems), where BNSF runs their longest-distance hotshots. We got pulled off once in Glasgow, Montana (150 miles into Montana’s seven hundred) with no consequences worse than a reluctant finger-wagging, and spent a couple days there, alternately getting wet in the first rain they’d had since spring, which arrived just in time to greet us, or hanging out in an abandoned building near the tracks with a doorway nearly barricaded with old radiators, torn-off wood paneling, that sort of junk. When we finally found a rideable train west one afternoon, we were so eager to board a nice grainer we found that we didn’t stop to fill our water bottles.

So only two crew changes further down the line, after a thrilling and ultimately sort of anticlimactic game of hiding from the brakemen in unfriendly Havre during the train’s “thousand-mile check” (we didn’t hear anyone get even very close to us before the train moved on), we bailed off to fill our bottles and wait for the next train in Whitefish, a ritzy tourist town just outside Glacier National Park, where people on vacation stop to buy all that nice gear they forgot to bring, at nicely inflated prices, before tramping on out into the wilderness. Again we hung out for a couple days, this time setting up camp near the tracks, on the verandahed loading dock of a disused blue building near the tracks, fenced off on three-and-a-half sides and sitting in the middle of a former gravel parking lot now grown chest-high with grass. During the day we stashed our backpacks in the neighboring empty lot and wandered around town, waiting until dark when we might be able to get on a train unseen.

The third morning we slept a little late, and woke up to a drizzle, and just sat there on the loading dock failing to work up the motivation to pack up our sleeping bags. And then a white truck drove into the little abandoned lot, and concealed police lights lit up from inside it. Busted.

The cop told us if it were up to him, he wouldn’t write us a ticket, but, he said, the city of Whitefish hates trainhoppers. It seems they ruin its bougie aesthetic. In fact sometime earlier that year one of them had pooped on the town green. Oogles. They ruin everything.

Trainhoppers draw a sharp distinction between decent trainhoppers, who just ride, and don’t open up the shipping containers or mess with the control levers when riding a rear locomotive or get rude with yard workers, and oogles, who do all these things and believe themselves to be the crustpunk lords of the road, wearing clothes that haven’t been washed in months composed mostly of punk band patches, dragging around big black dogs they can’t really care for, drinking Steel Reserve 211 and Night Train from morning to night, and speaking only in yells. An oogle was the one who spoiled Whitefish, or, to use the proper terms, blew up the scene.

Oogles or not, we were still busted, and had a $185 fine each to pay off. Later on, in November, while we were at Feral Farm, I sent a postcard from Dunsmuir (a hobo haven, though I wonder if they got the joke) to the Flathead County Justice Court, in fancy cursive and extremely formal language, to request a telephonic court date. So I had a little phone call with the judge, where I negotiated to pay the fine via community service instead. I have $185, but I decided this was a moral issue for me: which would I rather do, send them $185 that I could better use traveling, and further fill their county coffers already bloated with the taxes from stores that sell $500 coats to rich people—or do some good for the community and at the same time refuse to play their game the normal way?

As the end of sugarbush rolled around I realized that I couldn’t both go to Kalispell (the county seat) for my Salvation Army time and visit my parents in Ohio (total about 3800 miles) in the time I had (a month). So I took a chance and sent the court another postcard asking if I could do the service in Cincinnati instead, and then hitched to Cincinnati, where a day or so after arriving I got a call from a court clerk advising that’d be “fine”.

And so it was that I ended up working twenty hours at Matthew 25: Ministries, a strange place in Cincinnati. It’s a charity; it’s also a warehouse. They call up big companies and ask if they have any extra stock they suspect a charity could use. These companies have often been sitting there with lots of boxes in a warehouse somewhere, full of slightly imperfect shirts or possibly damaged incontinence pads, dreading when they finally have to pay to dispose of them, and here Matthew 252 calls and offers to take them off their hands for free, tax-deductible. When all these boxes come in, upwards of two hundred volunteers a day help sort the stuff (good from bad, this from that), move it around on pallet jacks, and load it all onto trucks, which take it to disaster relief efforts around the country, or to planes to ongoing humanitarian poverty relief efforts around the world.

It’s a very snazzy charity. Forbes ranks it as one of the “Most Efficient Large Charities in the US”. The warehouse is enormous, with motivational quotes painted large on the walls, and I saw someone guiding a group of suited people through, presumably courting donations. They even have re-creations of the places they send aid to, so they can walk people through on a virtual tour of the places they’re helping. Here’s what a place could look like just after a hurricane hits, the guide told us in a bored voice (he’d led this tour too many times), and sure enough off to the side was a life-size simulation of a building that had been reduced to slabs of concrete. Here are the kinds of conditions some people live in in the poorest parts of Appalachia, he said, and I saw a falling-apart trailer home with cricket noises playing and American flags inside on the table. It was a weird tour, and filled me with mixed feelings. But even though it behaves a little like an awful corporation sometimes, I think on the whole they’re doing pretty good work.

I sorted paint. Donated paint comes in from hardware stores around the city, and we volunteers open up each can, check if it’s usable, and then sort it by color into some big barrels nearby. I also sorted clothing donations, and moved pallets full of T-shirts around, and sorted new incontinence pads—busted-open ones from usable ones—so they could be used to mop up spills or as gauze or for anything else a hospital in (someone suggested) Jamaica might be able to use them for. And within two ten-hour days, I had enough hours to satisfy Kalispell. And you know, I suppose it was pretty satisfying. Even though I didn’t get to see the faces of anyone who benefited from my efforts, I know I actually did do something positive. Rather than just buy Flathead County a few yards of pavement.

Diagonal walks

It was weird to be back in Ohio. I hitched in from Minneapolis. One guy who picked me up was on his way from Colorado to New York, and dropped me off in Toledo, so I came in from the north. While crossing Ohio from north to south, I realized one of the reasons I had to move away from the state originally. There’s no wild space. Practically anywhere. It’s just field after field, punctuated by highways and more or less identical towns. I talked to a gas station attendant in Toledo, someone I could tell right away was very emotionally sensitive. I asked him what there is to do for fun in Toledo. Not much, he told me. Go to bars. Drive around. Hollow. No wonder about twenty-seven hundred people each year in this state take so much of an opioid that they die. And they’re just the ones who didn’t manage to stop short of dying. A guy who drove me toward Columbus, a lifelong local, told me Columbus was where the first strip mall ever was built. Ohio seems to be where most of the things I can’t tolerate about the US had their genesis.

Nothing’s not rectilinear. If not physically, then philosophically. The second day I worked at Matthew 25, I got dropped off about an hour and a half before they opened. I decided to have a walk around. To the Ohioan eye, there was a big warehouse and a parking lot. I was feeling Ohioan but suspected there might be more. I noticed the parking lot wasn’t quite level all over; there was a dip in the middle where a line of grates led across the lot. I followed the line of grates (paying only enough attention to parked cars not to wander into them) to the edge of the lot and found the drainage’s outflow. A concrete pipe stuck out from the dirt under the blanket of asphalt, and emptied down a muddy slope, into a churned-up patch of earth next to the parking lot, where earthmovers were parked in anticipation of an upcoming groundbreaking ceremony for Matthew 25’s newest wing. Taking the opportunity to leave one last set of attentive human footprints on this living dirt before it’s put to sleep for the lifetime of the new building, I walked around the corner of the building into grass, which grew in pleasantly irregular patches on non-level ground, and I looked out over the trees stumped and to-be-stumped in the footprint of the new wing. When I rounded the next corner of the building I found myself in a narrow passageway between the building and the bushy fencelines of the next property over, shaded over with trees, where birds had taken up residence in the branches. Even though I followed a straight line between the building and the fencelines, I could feel the rectilinearity untautening through the gentle knot-picking fingers of the irregular and strictly contingent cloud of budding branches above me. And in its place seeped back the old familiar chaotic warm complexity of nature. I was a citizen of Earth again. The endless tessellation of the squares of Ohio make it hard for to remember that I belong in the world. When I walk in wild places I remember I am an animal.

If I lived in Ohio I would probably get in trouble for needing constant booster shots of this knowledge. On my way into Cincinnati, when I got dropped off in Toledo, the guy left me at a bad interstate onramp, all local Toledo traffic. I walked south parallel to the interstate on the Dixie Highway (also all local), five miles past a sand supplier and a pet daycare and the construction of a megachurch and a giant greenhouse surrounded by crew-cut lawn on “Progress Drive”,

then turned left and walked another mile and a half to get to the next I-75 exit, Middle of Nowhere. When the slow dribble of cars there declined to stop for me for three hours in a row (mostly sorry-I-can’t big-company truckers and, for some reason, people in nice cars amid the farms, who all seemed embarrassed to be there, like the balding white guy with a license plate that said SUCESFL—well I didn’t want to ride with you either, how’s that?), I gave up on Middle of Nowhere.

Another six miles south I knew there was a town, Bowling Green, where at least I could get ignored by more people, some of them college students. But the thought of walking a mile and a half back to the Dixie Highway just to even get started, when I already had blisters, just filled my head with a cloud of no’s. So I went cross-country. Skied down the onramp’s embankment and skirted along some tilled brown acres not yet sprouting, cars brumbling past on the interstate a couple dozen yards away all safely contained by a metal deer fence and a windrow of pines along the edge of the farm. At the far side of the farm I hit a difficulty, a deep drainage ditch separating this farm from the next one, but neatly got around it by climbing up on the fence, which stretched across the ditch, my 50lb backpack dangling off my back as my weight twisted the fence toward horizontal, and crabbing across. After another couple farms, I reached a railroad track, which I followed diagonally toward Bowling Green, getting confirmation that it headed there from a man whose small fluffy dog attempted to intimidate me away from his front yard. I found another road that went due south and attempted to shortcut into town, but when I disbelieved a no outlet sign (I can climb over whatever the obstacle is at the end of the road) I was disappointed to find the obstacle was an airport, the one thing I wasn’t willing to trespass across. So I backtracked and ended up following a road that ran along the tracks anyway, right into town. I found the interstate, but I wasn’t on a street with an onramp, but I waded a creek and, still barefoot, headed south dodging goose poop through a golf course, and that problem was soon solved too. I had walked, all told, sixteen miles in the day by the time I reached a gas station at the Bowling Green onramp and flopped down to eat hot dogs and a milkshake that, I felt, I richly deserved. But damn if I wasn’t happy as a clam for all that. (And I got a ride nearly as far as Columbus that evening, too.)

When I was a kid in Cincinnati the park I hung out in most was accessible by means of entrances that all had no trespassing signs on them. I never let that bother me. Land is land. The oaks and maples are the ones to ask for permission, the honeysuckles, the Queen-Anne’s-lace, the teasels. What some human in a distant office has to do with it is beyond me. That’s why I’d probably get in too much trouble in Ohio to stay there. When well over 99 percent of the land is sectioned into rectangles enclosed in fences that say keep out, the only sane human response, as far as I’m concerned, is to disregard the signs and go hang out with the land.

Time off

After I beat my mom and grandma a number of times at Scrabble, and gave my dad a birthday present, and roused some very minor rabble with my old high school friends, I rode back to Minnesota on buses.3 I had to get back in time for my three-day meditation retreat. Last May I did a four-day fast in the Anishinaabe tradition in Canada (which I still intend to write about, but haven’t yet); this year, it seems, it was time for me to meditate in the Buddhist tradition instead. Sprout House, where I used to live in Minneapolis, has a long history of people who live there going to Common Ground Meditation Center, a place founded about 25 years ago in the Vipassana tradition, now housed in a peaceful little building in an old warehouse district. Common Ground regularly puts on retreats, which anyone is welcome to go on, thirty-odd people at a time meditating in all-day silence at a place that Common Ground has had a relationship with for years. It used to be a Franciscan monastery, but just this year was bought by some Sri Lankan Buddhist monks who decided to keep the relationship going.

When I heard it was a monastery I imagined the one I stayed at in Galicia when I walked the Way of St James: built of stone weathered to soft shapes over hundreds of years, cavernous interiors hung with draperies where the stone absorbed all sound. Well, Metta Meditation Center is a typical Midwestern structure with beige vinyl siding and brown shingles, drywall and institutional gray carpet. The staircase banister is lovingly made of crosses left over from the Franciscan sisters, and there are posters still showing Jesus now joined by Buddhist ones, but otherwise you wouldn’t know. It is, though, in an extraordinarily peaceful place, a peninsula on a lake providentially called Elysian Lake (a name tempered a bit, for me, by the farm runoff that, I was told, makes your skin tingle for several hours if you try swimming in it), surrounded by puffs of sumac groves and hilly old windswept forest, traffic a far distant echo of another world’s thought.

I spent three days and three nights there, trying to remember how to meditate, how to clear my mind of all its temporal things, listening to people speak about the teachings of the Buddha. And I felt like a stranger. I’ve gotten a lot of Buddhism secondhand, but so rarely learned anything about what the actual Buddha said, and here I was now imagining the India of 2600 b.c., which I knew nothing about.

Something kept echoing in my mind—a friend of mine, another student of Pebaam’s, told me he was studying Lakota tradition until his teacher passed on, and that teacher had told him you don’t just mix and match spiritual traditions. You have to pick one and dig in deep, respect it and have humility about how much you think you know. Otherwise things that are supposed to interweave and make sense together won’t connect, and you’ll find yourself knowing possibly even less than when you started. “Don’t cross the pipes,” he said. After so long learning Anishinaabe traditions, when I sang,

- Buddham saranam gacchami,

- Sangha saranam gacchami,

- Dhammam saranam gaccham,

instead of

- Biindigen,

- Zhaawanogaawi-asemaa;

- Biindigen,

- Waabanowi-asemaa;

- Biindigen,

- Ogimaawi-midewi-asemaa,

I felt like I’d woken up in an unfamiliar room.

But on the other hand, I did experience some amazing moments, like when, my legs going numb, I finally lit up with the constantly-sought dissolution of the border between myself and the rest of the world, and melted. As well as some deep frustrations, like all the walks through the big gentle forest and out to the far side of the peninsula while I tried and tried to remember how not to analyze, it’s so simple, why can’t I get it, and mostly ended up analyzing why I was analyzing.

On balance, I think it was good that I went. I remembered what it is to slow down. I remembered what it is to pay attention and be fascinated. I asked one of the teachers about all that analysis, too, and about how to just watch my thoughts go by, to use the usual metaphor, like they’re floating on a river, rather than seizing them and analyzing them. She pointed out that one can watch one’s own analysis when it comes up, and just let that float on by. Somehow it had never occurred to me. Buddhism may not be the path I’m taking right now, but I think the little detour did me some good even if it confused me a little.

Destination-optional

After meditating I stayed with my Sprout House friends for a few days, going on forays to bike shops to amass enough gear to take on a self-supported long-distance bike trip. (I’ve learned that the word serious bike people will understand for what I’m doing is “touring”. I use this word when I’m talking with serious bike people. When I think about it, I think about a “long-distance trip”.) One of the Sprouts, David, happens to be a bike mechanic, so I was in the right place, and he was almost unbelievably generous with his time, doing several hours of gruntatious manual work with me and asking in return only “a single baked good of your choice”. (Frosted cranberry scone.)

After three or four days, I was all ready to pedal off to Canada to help Pebaamibines build his new cabin. Construction would be throughout May and June, so my figurings were, I can show up and work for two weeks or so just about any time I get there.

Then I got a call from Pebaam: the plans had changed, and construction was going to start more like the first week of June. Maybe.

Well. Well I’d already gotten all ready to go to Canada, and I’d found some awesome paths to get there, and interesting places to stop on the way. I reflected that since the journey is the destination, if I don’t have a destination, I’ll still be getting somewhere. And so on May 12th, I piled my bike to a wobbling height with a modified version of all my vagabonding gear, and struck out northward.

I left at noon and stopped only twice, besides short breathers: once at a bike shop that appeared on my path, to get some equipment to stop my load from wobbling and distribute it between the front and the back (instead of loading down my back wheel), and once at a gas station where I restored my failing energy with two apple fritters for $1.20 and watched cottonwood fluff play around my legs. It was nine o’clock when I rolled into ARC, where Misty still lives, my first planned stop along the way, seventy miles later and three-quarters collapsed, barely able to climb up the stairs. I had left too late and hadn’t given myself time for breaks. Seventy miles nonstop is too many.

But on the way, I had an amazing time. The first day was a shake-out period for problems with the gear setup, but once I rejiggered the load at that bike shop, there weren’t any more problems, so I just enjoyed the Hardwood Creek/Sunset Prairie Bike Trail, twenty-two miles of former Northern Pacific railroad grade paved by two counties, threading between I-35 and US-61 and neatly far enough away from both that I rarely had to listen to them. Instead I got to sniff cherry blossoms and watch horses and cattle graze. Spring has at last arrived in Minnesota, and it’s making up for lost time. The weather is the cloud-tempered sun and breezy warmth that makes a whole Minnesota winter—even this year’s with its two feet of April snow—feel worth it. The frogs are peeping up a thunderous chorus. The small towns I passed through—Hugo, Wyoming, North Branch—seemed clean and newly minted. This is going to be a good trip.

I’ve been at ARC a few days, at first just recovering, then hanging out and giving tattoos. It’s become known that I do tattoos. I gave one yesterday to Medora, another ARC community member, an epic ten-hour fern (stick-and-poke is much slower than with a machine), and after I finish writing here it’s Misty’s turn.

“I feel like it’s always been there, but now other people can see it too.”

So I guess I’d better get to it.

-

After I left, naturally, the season finally started in earnest, and despite a 15-inch blizzard on April 14–15, they brought the total up to forty-five gallons, and everyone who came to get some at the closing ceremony left happy. ↩

-

Matthew chapter 25, if you’re curious, is where you’ll find the phrase “Inasmuch as ye have done it unto one of the least of these my brethren, ye have done it unto me” [KJV, 40]. Incidentally, Jesus was in an apocalyptic mood when He said this, and immediately went on to tell those who didn’t do anything for the least of us that come Judgement Day they’d have to “Depart from me, ye cursed, into everlasting fire” [KJV, 41]. (And a little earlier on, takes a bit of a departure from His usual advocation for the poor to let us know that “whoever has will be given more, and they will have an abundance. Whoever does not have, even what they have will be taken from them. And throw that worthless servant outside, into the darkness, where there will be weeping and gnashing of teeth” [NIV, 29–30]. The chapter as a whole seems decidedly not the best one to single out in the Bible.) ↩

-

Think I’m done with Greyhound, by the way. I won’t catalog all the indignities and miseries I’ve experienced from them, but I will say I would’ve preferred to hitchhike. In the rain. Via Alabama and Kansas. And get rides from people with tiny cars who spent the whole time complaining. ↩

File under: Year of Listening, Anishinaabe, snow, religion, family, biking, tattoos · Places: Minnesota, Midwest

Note: comments are temporarily disabled because Google’s spam-blocking software cannot withstand spammers’ resolve.

2 Comments

Verne Troxel

HistoryYou have interesting travels

Aunt Jerry

HistoryLove reading your posts.